Former Sheriff Kills the Sheriff of Douglas County 1879

Wed, 09/07/2022 - 12:56pm

admin

By:

Lou Wehmer

Howell was not the only southern Missouri border county to suffer post-Civil War violence and civil unrest. Both sides had committed atrocities, and the tendency to take the law into one’s own hands was prevalent among the population supposed to be at peace. The 1879 tragedy of the killing of the Sheriff and former Sheriff of Douglas County exemplifies how unsettled things remained.

In the case of the powerful Alsup family of Douglas and Howell counties, their conflict with others predated the Civil War and developed into a feud. The war intensified the hatred, and in the post-war period, it developed into an “Alsup or Anti-Alsup” sentiment along the lines of Union versus Confederate or Radical Republican versus Democrat.

As late as May 1888, a couple of decades after the feuding had ceased, the Springfield Express wrote an article about the cost of recent court cases reported to the Missouri State Auditor. He stated, “The Alsups of Douglas County have cost the state nearly $100,000 in the last twenty years for criminal costs.” The cost in lives lost was worse.

Though different sources give different reasons for the warrant being issued for the arrest of James Shelton “Shelt” Alsup, the evidence is he did not like the current Sheriff unseating him from his former job. Shelt had served two terms as Sheriff/Collector in 1874 and 1876 and avoided arrest several times during his tenure because of his position. In 1878 a new Sheriff, H.H. Vickery, was elected and took office in 1879 under a campaign promise to arrest anyone for which a warrant was issued. The Forsyth Pioneer newspaper, under the title, “The Trouble in Douglas County,” informed its readers on February 14, 1879, of the problem. They wrote, “An action is pending in the circuit court of that county against the present county collector, J.S. Alsup, and his securities on his official bond, for money collected by him which he failed to pay over and account for.’

‘He has employed as counsel a young man by the name of M.H. Griffith, who, we are sorry to admit, represents himself as an attorney at law. Mr. Griffith, about two months ago, got permission of the clerk of the county court to take the record book into his office, representing to the clerk that he wished to copy some entries relative to Mr. Alsup’s settlement to send to some of his associate counsel, and his office being in an adjoining room the request was granted, and the record kept out all night, during which time Mr.Griffith took two leaves containing a settlement of Mr. Alsup as collector from the book and put two other leaves in their place containing such entries as he thought was beneficial to his client. This changed the records so that Alsup would come out all right on trial. But unfortunately for the Colonel (Mr. Griffith), his handwriting was identified, and he was arrested for the crime. He also made a number of other changes in the record to suit himself and his employees.

When arrested, he at first denied the charge, but before the day set for the hearing confessed the whole matter, and when his case was called for hearing one-day last week, he went into court and pled guilty to the charge. He also told and filed an affidavit to the same effect that Shelt Alsup and William Alsup employed him to make the changes in the records and agreed to pay him the sum of five hundred dollars for the job. A warrant was issued for them and placed in the hands of the Sheriff, who, in company with five others, went to make the arrest. They came up with Shelt Alsup on Fox Creek and ordered him to surrender, but he happened to be on Easter, his celebrated race mare, and didn’t see fit to obey, so he put spurs to his mare amid a shower of balls from the Sheriff’s posse made his escape unharmed. The Sheriff failed to find W.N. Alsup, so neither of them up to noon of the 13th instant had been apprehended.”

Shelt avoided the law just five days until September 18, 1879. Twenty years later, the Springfield News-Leader summarized the events leading up to that fateful day. Under the title “IS BUT A MEMORY NOW” and “Fiercest of All Ozark Mountain Feuds,” they told their readers, “The famous Douglas County Alsup feud, the fiercest factional war ever fought in the Ozark Mountains, is now only a memory. Most of the old leaders on either side of the bloody strife are dead, and the lapse of years has softened the spirit of vengeance in the hearts of their descendants until today, these younger representatives of the once hostile factions can meet without the prospect of a battle.”

“Twenty years ago, the Alsup feud was the terror of all Douglas County. The influence of the war was felt throughout a large territory beyond the borders of that county, and Alsup and anti-Alsup partisans could be found from the head of Beaver Creek to White River. The Alsups were a strong family both in numbers and in force of character. They were old settlers and had more property and intelligence than the average class of pioneers of that section. The family had made a conspicuous record in the Civil War, all being fearless defenders of the Union cause.

One of the men who took an active part in the bloody and ruthless guerilla warfare that ravaged the Missouri and Arkansas border from 1861 and 1865 was captured by rebel forces and subjected to the most cruel outrages. He was a giant in strength, and his captors harnessed up their prisoner and made him do the work of a horse in a bark mill.”

Here the writer is referring to Ben Alsup, who lived before and during the Civil War at the south end of Willow Springs. Ben was kidnapped from his home at the beginning of the war and held and mercilessly worked as a prisoner for the whole duration of the conflict. His story will require another article.

“After the war, the Alsups took possession of the Douglas County government (and Howell County, too) and had things their own way about Ava for a number of years. Their large following and superior intelligence of the men made the county seat “ring” restless, and year after year no one could be elected without the favor of the Alsup faction. When at last the opposition to the Alsup rule became formidable, and office-holding brotherhood rested the attack on their courthouse privileges with the most bitter spirit, and then the war began.”

“The complications of the feud increased as the fight went on, and finally, the whole county seemed more or less involved in the strife. It would make a long story to tell half of the bloody incidents that grew out of this deadly war between the Alsups and their personal and political enemies. The killing of Shelt Alsup, then the leader of the faction, and the Sheriff of Douglas County, was one of the most tragic scenes in the history of the feud.”

“The fight occurred about daylight at the home of Alsup, the Sheriff being assisted in the attack by a posse of nearly a dozen special deputies summoned for the hazardous enterprise. Several men had already been killed on both sides, and it was known that Alsup would not surrender to his enemies without a fight. The Sheriff and his posse selected the early morning hour for the attack in order that they might surprise Alsup at home, hoping to get his house surrounded before being discovered. This part of the plan was successful. The Sheriff and his men slipped up to the house while Alsup was in bed. All was still within the little frame building when the officer and his deputies took position for the expected battle. Then the Sheriff knocked at the door and informed the awakened proprietor that he was wanted as a prisoner. Shelt Alsup had no thought of surrendering. He had a small arsenal of guns and pistols in the house and, without taking time to put on his clothes, prepared for battle. A short parley preceded the fight. The Sheriff told Alsup to send his wife and children out of the house. The woman refused to leave her husband and defied the officers. The shooting began.”

“The Sheriff and his men sought protection behind the corners of the house and shot through the windows whenever they could get a glimpse of the enemy within. Alsup blasted away at every puff of smoke he saw. The house was a thin structure of weatherboarding, and the attacking party shot through the sides of the building without seeing the enemy. The Sheriff seized a big stone and was pounding a stone in the weatherboarding near the corner where he stood. He thought the studding of the house in the corner would protect his body from Alsup’s fire. He was deceived. A rent had already been made in the boards, and the officer swung his rock once more to enlarge the opening. Alsup was watching the breach in his fortress.

As the officer reached around from his hiding place to complete the work, he exposed a vital part of his person. A shot from Alsup’s gun killed the Sheriff instantly. But, the fight went on. The Sheriff’s posse now resolved to avenge the death of their leader. All thought of the majesty of the law was forgiven. The men fought for revenge only. The house was riddled with bullets. In the storm of the battle, Alsup’s wife ran out of the house and seized the dead Sheriff’s pistol. An infant baby on the bed was killed by the merciless fire. The mother saw the dead child and, taking its bloody body in her arms, rushed out into the yard and showed it to the assailants and begged for mercy. But the men paid no heed to her frantic cries. The distracted mother retreated back into the house, and the battle continued.”

“At last, Alsup, riddled from head to foot, could fight no longer and fell on the floor dead. He had been struck by over 50 bullets and buckshot. Every article of furniture in the house bore evidence of the fight. The bed on which the infant lay when killed was perforated with shot, and the bloody feathers scattered over the floor. Alsup’s shoes which he had not time to put on, were so shot to pieces that the tops drooped over like they had been leather strings.”

“The death of Shelt Alsup was the beginning of the downfall of the dreaded faction. From that time on, nemesis seemed to pursue the family. The relatives and other followers of the slain leader made a stubborn fight to recover their lost power in Douglas County, but public sentiment had turned against them. The killing of the child embittered the feud on the Alsup side, but the “antis” disclaimed any responsibility in the matter and excused the tragedy as an unavoidable occurrence of the fight. At a trial at Ozark, sometime after the death of Shelt Alsup, where a change of venue had been taken in one of the cases growing out of the feud, the courthouse was crowded with the opposing factions, armed for battle. One of the Alsup party denounced the opposition as “child killers,” and a dozen pistols clicked in an instant. The judge hastily vacated the bench, but the expected encounter was prevented by the friends of peace.”

“At the next election after the killing of Shelt Alsup, one of his brothers was assassinated while riding home from one voting place to another. His slayer was never discovered. The last of the old fighters on the Alsup side was drowned in a pond in Mountain Grove. The memories of the feud are now hardly felt in the politics of Douglas County.”

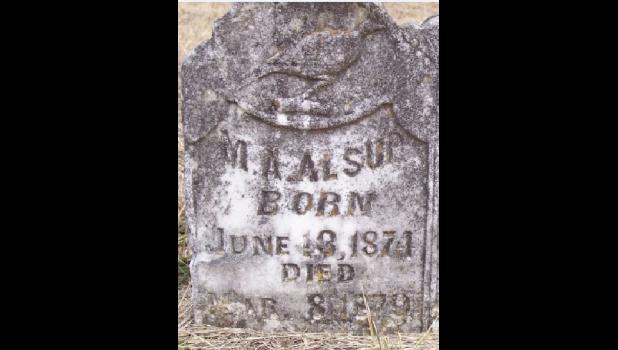

Shelt Alsup was just thirty-four years old when killed with his daughter Mary, age five, and are buried in the Denlow Cemetery, Douglas County. Sheriff H.H. Vickery was buried the next day in Ava, “his remains being followed to their last resting place by the largest concourse of people that ever assembled together in Douglas County.” (From the Marshfield Chronicle, March 19, 1879.)