Home from Pismo Beach

Tue, 08/10/2021 - 3:21pm

admin

By:

Lonnie Whitaker

The previous article, “Wrong Turn at Pismo Beach,” ended with losing my merchant seaman’s license on the beach in Miami, Florida, when I was supposed to be in Houston, Texas.

To recap, in 1967, the summer after my sophomore year at Mizzou, my stepfather had arranged for me to acquire a merchant seaman’s license and get aboard a ship out of Houston. Instead of going directly to Houston, I detoured to Florida to visit my former roommate, Lynn Spence, and ended up losing my wallet, money, and seaman’s license on the beach.

The next morning Lynn and I returned to the beach administrative office to check the lost and found department. Surprisingly, a good Samaritan had turned in my wallet, with no money inside, but, amazingly, it still contained my merchant seaman’s license.

Lynn, true to his word, loaned me money for a plane ticket to Houston, and a little extra to tide me over until my ship came in.

I landed in Houston, clueless as to how to get to the waterfront. A map on the wall informed me it was too far to walk. After asking for directions, I hoisted my seabag on my shoulder, found a bus stop, and headed for the waterfront. In an hour or so, I stood in front of the Harrisburg Hotel, a place my stepfather regularly stayed.

The Harrisburg Hotel would never appear on a Houston tourist brochure. It had been converted from a two-story house to a sleeping room establishment. A hand-painted sign above the front door announced, “Rooms, $1.99 for 24 hours.” I forked over two bucks, and the desk clerk showed me a room on the second floor and pointed to the communal bathroom a few doors down the hall.

The room matched its low rent, with a bare wooden floor, peeling wallpaper, a sagging bed in an iron frame, and a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling by an electrical cord. A wooden chest of drawers provided the only other amenity.

My first night, a group of hoodlum-looking young men, who loitered in the vacant lot across the street, hauled the soda machine from the lobby over to “their” lot and robbed it. Apparently not satisfied, they broke into the room next to mine. I never heard a thing. The clerk told me about it the next morning, and the soda machine was still in the lot across the street.

After a cheap breakfast, I headed to the seaman’s union hall and found “Mr. Jones.” He motioned me into his office. He did not look like a happy man. “Where have you been?” he asked. “You were supposed to be here last week.” He continued speaking over my attempted explanation. “There’s a longshoremen’s strike going on. I could have gotten you on a ship last week. Now, nothing’s going out.”

Mr. Jones told me the only thing I could do was try to wait it out. For nearly a week, I hung out at the union hall, waiting and playing cards with the landlocked sailors. But the strike never ended before I ran out of money. I had no choice but to get back home.

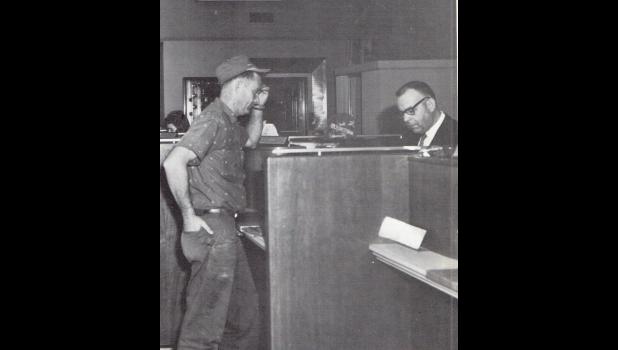

At the time, credit cards were virtually unknown. All I had was my checkbook for the Bank of Willow Springs. I called my brother, and he agreed to put some money in my account, but I still needed to get an out-of-state personal check cashed. Several blocks away, I found the Harrisburg Bank and told the teller I wanted to cash a check drawn on the Bank of Willow Springs. My request exceeded her authority, and she directed me to the vice president’s office.

I explained my situation to the vice president. He did not seem impressed. In fact, he seemed suspicious. My only identification was a merchant seaman’s card and a check from some small town in Missouri. He warned me about the penalties for writing a bad check, but he agreed to call the Willow Springs Bank. I told him to ask for Joyce Burns or Eddie Ogden, Jr. I felt sure either would vouch that I was not a crook. One benefit of growing up in a small town is you know the town fathers, including the bankers. And with bankers Joyce Burns and Eddie Ogden, their children were my schoolmates.

Since this was also before telephone direct-dialing, he had his secretary contact the operator to get the number and place a long-distance call. Only in small town in the Ozarks in the 1960s could this happen—the bank’s number was busy. For whatever reason, perhaps because my story was too strange to have been concocted, he agreed to cash my check without placing another call.

I flew standby to St. Louis and made my way to the bus station downtown and bought a ticket to Rolla. After midnight, I got off the bus at the Rolla bus depot. Within minutes, a Rolla policeman approached and began questioning me. He told me to get into his cruiser, and then drove south to the city limits on Highway 63 and told me to get out.

In the early morning hours traffic was sparce, and the drivers who passed by ignored my extended thumb. Around 2 a.m., a man driving a truck with stock racks stopped and asked me where I was going. When I told him, he said, “Get in. I’m headed to West Plains.” The truck bed was empty. He was returning from delivering a load of hogs to Chicago. I could have guessed that from the smell that still lingered. Nevertheless, I felt fortunate.

Sometime after sunrise, he stopped his truck in front of my house on High Street. My visibly annoyed mother met me at the door. I don’t remember the conversation, but I still remember how she looked. And one thing I knew for sure, I needed to find a summer job.

My buddy Royce Yardley (WSHS, 1966) was in town, and we made a pact that we would work together hauling hay and doing other manual labor jobs. I envisioned a long, boring summer, but within a few days, I received an unsolicited phone call from a director of the St. Louis Area Boy Scouts. He wanted to know if I had a Red Cross Water Safety Instructor’s license. When I told him I did, he offered me a job as the waterfront director at Beaumont Scout Reservation in rural St. Louis County.

I agreed to accept the job, provided he would also hire Royce as a lifeguard. Royce had a Red Cross Senior Lifesaving certification. Sight unseen, on the basis of a telephone interview and my recommendation of Royce, he hired us both for the summer.

So, my wrong turn at Pismo Beach had a happy ending. Royce and I spent an interesting summer teaching swimming and lifesaving lessons at Beaumont Scout Reservation. But to this day, I regret missing my great sea adventure. Oh, the stories I could have told.