More Tales From Country School Days

Wed, 10/07/2020 - 12:09pm

admin

Like Sherlock Holmes, the fictional English detective, I have an older, smarter brother. Jack will admit he is four years older but deny that he is smarter. Nevertheless, my observation is true. Generally, this has proved to be a blessing, but at times during my childhood, I would have cringed at such a notion.

Consider the “Case of the Vanishing Cupcake.” My grandmother was a wonderful cook. I still recall the smell of homemade bread baking in the woodburning cookstove. Bread, which would be topped with butter, churned from the milk of our Jersey cow. But my favorite of her baked wonders were cupcakes—and my brother knew this.

One afternoon in our back yard, when Jack saw me staring at the freshly-baked cupcake in his hand, he lifted it to his nose, inhaled audibly, and said, “Hmmm, this smells good.” He had my rapt attention. “Let me have a bite,” I pleaded. With both hands, he clutched the cupcake to his chest as if he were protecting a baby chick from a predator. “No,” he said, “you’ll eat the whole thing.” I promised to only take a nibble. “Okay, then, just a tiny bite,” he said, and handed me the cupcake.

With the gusto of a hound dog, I crammed half of the cupcake into my mouth. Before my brain could inform me that something was wrong, I started gagging and coughing. My stomach convulsed and my eyes watered, as I tried to spit out the cupcake. He had filled it with red and black pepper. I don’t recall if he got in trouble for his shenanigan, but I suspect Grandma only mildly admonished him. But then, he was always her favorite. Harrumph.

And then there was the case of “The Mysterious Card Trick,” when I was a gullible 9-year-old. With TV generally unavailable at the old Shannon County farmhouse, Jack and I often played card games with our grandparents. The usual game was Pitch, but Jack and I also played a game called “Drink or Smell,” which we learned from an old cowboy movie—but that’s another story. The point is, we were always fooling around with a deck of cards.

Somewhere, Jack had learned a card trick. After shuffling the cards, he’d fan them on the table and have me select a card, and without showing it to him, return it to the deck. After apparently reshuffling, he would identify the card I had picked. I pleaded with him to tell me the secret to the trick, but he refused to tell me.

Finally, after persistent begging (and probably after promising to do some of his chores) he said, “The secret to the trick is you smell the cards.” Even as naïve as I was, I was skeptical and accused him of fibbing. But with pokerfaced righteousness, he assured me he was telling the truth. To prove his point, he raised the Ace of Spades to his nose and sniffed at it. “The aces smell like gravy,” he said, and handed it to me to smell.

My brother, like any conman worth his salt, knew that a victim’s downfall hinges on the desire for the gimmick to be true. I took the ace from him and, by golly, I thought the card did smell a little bit like gravy. Then he told me the kings smelled like oranges, and that all I needed to do was practice. And somehow, the trick seemed to work when Jack picked the card.

[Note to readers: At this point, I have abandoned any attempt to edit the story so I don’t look like a complete nitwit.]

I practiced, sniffing and shuffling, until I was beginning to believe the trick actually worked, and could hardly wait to show off for my buddies at the Montier school. The next day, I hid the cards in my pocket and smuggled them onto the school bus. I figured I had to be sneaky because one boy had gotten a whipping for bringing chewing tobacco to school, and I imagined a deck of cards might be a worse infraction.

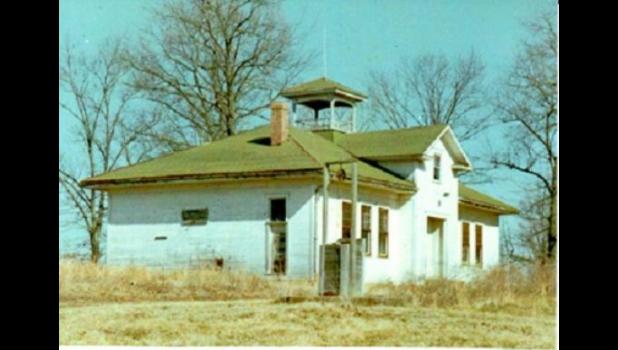

The schoolhouse at Montier, based on old photographs and correspondence I have, was built before 1920. The interior of the white clapboard structure, behind the kitchen and cloakroom at the front, had a large central area divided into two classrooms by a heavy wooden folding door. On one side, which was referred to as the “Little Room,” Mrs. Margaret Shockley taught grades one through four. On the other side, her husband Wilbert taught grades five through eight in the “Big Room.” My brother was an eighth-grader in the Big Room.

That morning before recess, and my opportunity to demonstrate the trick, a student from the Big Room came over and told Mrs. Shockley that Mr. Shockley wanted to see me. My mind went to full-alert status. “Did he say why?” Mrs. Shockley asked. The student indicated that he hadn’t.

I proceeded to the Big Room, and all four rows of students—each row a separate grade—watched as I entered. Mr. Shockley motioned me to his desk and said, “I understand you know a card trick.” With some hesitance, I told him that I did. “What’s the secret to it?” he asked. An anxious feeling hit my stomach, and, no doubt, with a tentative voice, I told him that it involved smelling the cards. At that point, all four grades broke into uproarious laughter.

Needless to say, at that moment I wanted to crawl inside a hole and disappear, but a sudden awareness struck me: the real secret of the trick was that I had been tricked. The fortunate thing about childhood attention spans is they are short lived. At recess, some of my buddies laughed, others expressed sympathy, but after lunch I don’t recall the matter ever being mentioned again.

It is unlikely that latter day teachers, including me, would set up a student for public embarrassment. But surprisingly, that incident never sparked a resentment of Mr. Shockley. He teased everyone, and I still consider him one of the best teachers I ever had. However, the “Case of the Purloined Note,” which I will save for another day, did get my dander up.

But there are blessings from the cases of the “Vanishing Cupcake” and “The Mysterious Card Trick.” If I am ever accused of being a suspicious, cynical curmudgeon, I can blame it on my brother.