The Telephone Comes to Howell County

Wed, 01/13/2021 - 12:13pm

admin

By:

Lou Wehmer

Many worked on the idea worldwide, but Alexander Graham Bell was the first to be awarded a successful patent on the telephone in 1875. The utility of his device wasn't immediately seen but soon caught on, and by the turn of the century, phone service reached the Ozarks.

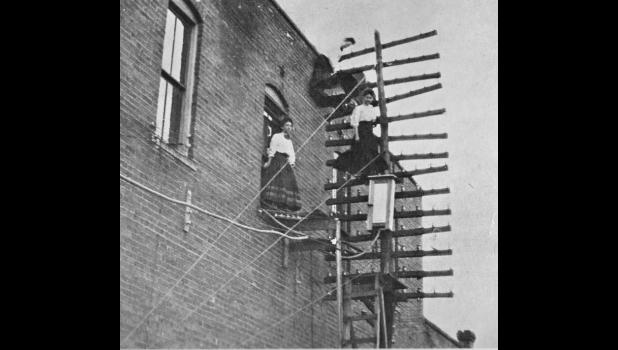

In Howell County, development was initially driven by the railroad, which was already using the telegraph to control their rails' traffic. A county history states the telegraph arrived on our rail lines in 1884, and telephone lines were first installed in the late 1800s. Some early West Plains Quill articles speak of expanding telephone service into town in an office on Washington Avenue in 1900. In 1908 the telephone "central office" was moved to the second floor of the Aid Hardware building on the square. Photos of this period show poles with multiple horizontal wooden arms holding a multitude of single lines. With the move to the Aid building, an attempt was made to use multiple-wire cables. Doing so helped solve a developing problem where the fledgling electrical power system attempted to use the same poles. The two types of wiring did not mix, and when they accidentally came together, they often caused fires or electrical accidents.

Jerome Boyer acquired the West Plains Telephone system in 1911. In 1914 the West Plains Telephone Office and Aid Hardware Building were destroyed by a fire in the phone office. The central office was rebuilt in Colonel Jay Torrey's "Little Fruitville" office on Walnut Street, where it remained another thirty-five years. The Little Fruitville building was located where the Murrell's Cleaners building is today.

According to local historian Ella Horak, "Mr. W.N. Wicks installed the first telephone exchange in Willow Springs in 1904. The central office was in the second story of the Vooher's building, at the corner of Second and Center Streets." For current readers, this is the vacant building location that housed the "Corner Bar." Wicks was also engaged at various times in Willow Springs' water and electrical power systems and gained enough prominence in the community to win election as Northern County Judge (County Commissioner.) He sold his interest in city utilities, including the telephone, in 1906.

A relative of Ella Horak, Roy Forest Lilly, installed Pomona and Hutton Valley's fledgling phone systems around 1909. Lilly was just out of high school and later became manager of the Western Electric Telephone Company for thirty-four years. After high school, Lilly attended Drawn's Business College in Springfield but was more interested in electricity. Ella wrote of her nephew, "When he returned to Pomona, plans to put in phone lines and the switchboard was in the making. He installed the switchboard in Pomona, connected the lines, which at that time wouldn't have been too many. His next job was to put in a switchboard at Hutton Valley. He installed it in the John Gulley home, and farm lines were built. The big-box phones were fastened to the wall, and rings were made by a short-long-ring system, as long-short, two shorts, one long - and so on, for every line. When a person wanted to call a neighbor, every phone on the line rang. Oh, yes, we could hear the receivers being hung up. The phone was operated by turning a little crank on the right side of the phone box."

A single turn of the crank generated the short ring and the long by several turns. A standard convention for an emergency was to crank six longs. By then, you should have had everyone's attention on the line and several listeners to what you wanted to report. However, on a long line with lots of listeners, the line could be overloaded, and a fuse would blow, taking the entire line down. The system left a lot to be desired.

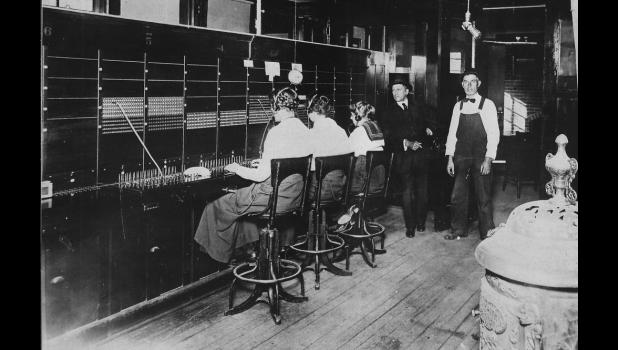

Phones in the early 1900s required their own dry cell batteries. The "little crank" on the phone box turned an electrical generator that sent a higher voltage on the line to alert the central office you wanted to make a call. The operator plugged into your line and asked, "number please," and patched your line into the line you wanted to call. After the 1914 phone office fire, the West Plains system was switched to a common-battery switchboard, eliminating the need for batteries on your phone. Voltage from the switchboard alerted the operator with a light when you picked up your phone receiver. The operator asked for the number you wanted to call.

A common use of the old phone boxes' generators was to remove them and put their wires into a pond, stream, or lake. The cranking voltage generated was sufficient to shock fish underwater and stun them to be collected on the surface. Game wardens soon outlawed that practice. I also recall getting a group of kids to hold hands with the persons on each end holding a wire, giving everyone a shock. Oh, the good old days!

Growing up in Willow Springs in the 1950s, before rotary dial telephones, I recall picking up the telephone handset and hearing the operator say, "number please." Our home number was 254.

It was years before rural electricity was installed, and often a single phone line served dozens of customers. In 1975, when I moved to the Hutton Valley community to live, the only telephone line available was a "party line" with around ten subscribers. By then, calls were sorted by ringing frequencies instead of cranks, but many subscribers used telephones that didn't have this feature. When you answered the phone, many others answered with you and often listened to make sure the call wasn't for them. Or they were bored or nosey and just listened. I was just starting work at the Highway Patrol and had to receive special dispensation to live in a home on a party-line as all calls to and from the office were supposed to be private.

Initially, telephone exchanges were local, limited to calls in their exchange. Quickly efforts were initiated to build lines interconnecting communities. There were subscription costs or charges for using these lines initially, but soon area towns were interconnected, occasionally free of charge. In this area, West Plains became the central office to which surrounding towns wanted to be connected. From there, your call could be routed to Springfield for an additional charge, and from Springfield, routed anywhere in the country where there was service (for an additional cost.) Thus "long-distance" calls were relatively expensive but cheaper than a telegraph and much more convenient.

Every community or small exchange had its own switchboard in a central office and was mostly operated by female operators. These operators became well known in the community and were relied on in all kinds of emergencies, like fires. It was the operator's job to know who the volunteer firemen were and call them.

Because merely pushing a switch allowed the operator to monitor any call, a tremendous amount of trust was placed in them to respect callers' privacy.

The Mountain View Standard published this article in their December 4th, 1916 issue: "The telephone girl sits still in her chair and listens to voices from everywhere. She hears all the gossip; she hears all the news; she knows who is happy and who has the blues. She knows all our sorrows, she knows all our joys, she knows every girl who is chasing the boys; she knows all our troubles, she knows all our strife, she knows every man who is mean to his wife. She knows every time we are out with the boys; she hears the excuses each employs. She knows every woman who has a dark past; she knows every man who's inclined to be 'fast," in fact, there's a secret 'neath each saucy curl of that quiet, demure looking telephone girl. If the telephone girl would tell all that she knows she would turn half our friends into bitter foes; she would sow a small wind that would soon be a gale, engulf us in trouble and land us in jail; she could let go a story (which gaining in force) would cause half our wives to sue for divorce; she could get all the churches mixed up in a fight, and turn all our days into sorrowing night; in fact, she could keep the whole town in a stew if she'd tell a tenth part of the things that she knew. Now, doesn't it make your head whirl when you think what you owe - to a telephone girl?"

Most of the Howell County systems were initially created by individual entrepreneurs with their own money or by money generated by stock sales in their company. Mountain View had an unusual pathway to the creation of their local company. A group known as the Farmer's Mutual Telephone Company was created as a cooperative. Stock was sold, but the object was to keep the cost low for the individual subscribers, and profit from the system went back into the system instead of the individual investor(s). The plan worked well for several years, and subscriber costs were maintained at around fifty cents per month instead of a customary dollar to a dollar and a half monthly fee for most of the other area systems. For several years rural phone customers on the Farmer's Mutual Exchange received their monthly phone service for ten cents per month. The initial stock offering for the company known as the "Farmer's Mutual Telephone Exchange Company" occurred in 1910, and the central office and switchboard was installed in the "Reynolds Building" downtown. Later that year, it was moved to the J.E. Chowning home on Second Street, where it remained for several years.

A bit of controversy occurred in intervening years when the Mayor and City Council of Mountain View refused to allow Farmer's Mutual to use city power poles in alleyways in town. Because of the cooperative nature of the first system, the city neglected to arrange a franchise for the group to use town poles and when they asked the coop to fork over money for that purpose, they refused. A civil case dragged on for another eight years, until 1919 when the Missouri Supreme Court ruled in the coop's favor. As a result, in 1922, the city was forced to pay legal fees and penalties and, for a while, had to turn off street lights in town to save money to pay $325 still owed to the coop.

In 1909, the "Current River Telephone Company" was created to provide service along the railroad right-of-way to provide service to Birch Tree, Trask, Winona, and other small communities nearby. Service was extended as far south as Peace Valley, and interconnection was made to the Willow Springs and West Plains systems.

The nationwide Bell Telephone System soon reached the several private systems in our communities and provided better long-distance services, of course, at a cost. Smaller systems were bought out by larger ones, eventually being sold to large companies at the state and national levels. Only a few private telephone systems remain in Missouri, one of them being the Peace Valley Telephone Company, a privately owned system in Howell County since 1958.